Chinchilla Dystocia and Cesarean - A Case Study

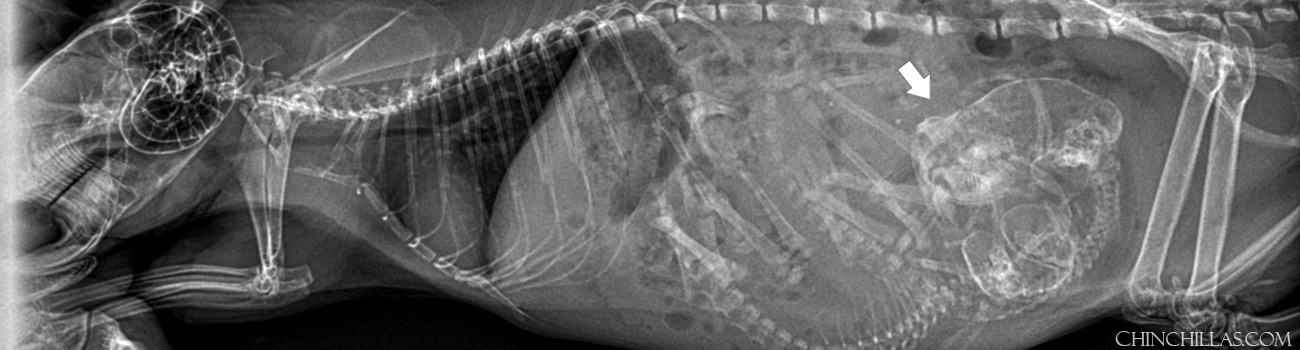

The pointer above shows the two kits still relatively high in the abdomen, after 6 hours of labor.

The majority of chinchilla deliveries go well, but it is not uncommon for a pregnant chinchilla to suffer from a dystocia. Without intervention, a dystocia may put the pregnant chinchilla at risk of death. However, improper intervention can worsen the situation, so intervention must be approached with considerable deliberation.

A dystocia is a difficult delivery. First time delivering mothers are more prone to dystocia, as are obese females, and females which may have been bred too young. Other causes of dystocia include mycotoxins, overly large kits, deformed kits, kits presenting in the wrong position or a breech presentation, and failure of progression (meaning the kits do not move down into the pelvis for delivery).

In the case of the female chinchilla pictured here and in the xray above, this was a first time delivery. She was two years old, and went into labor the morning of March 23rd, 2023. The kits were alive and moving at the onset of labor, however, there was a failure of progression. Despite hours of active labor, the kits had not moved down into the birth canal. After 2-4 hours of labor with no progress, the situation became more critical. The longer a delivery is delayed, the less likely it is that the kits will be born alive. An experienced owner or herd manager may attempt to turn the kits, or help pull the kits, but it takes skill and experience, and both carry risk. The administration of oxytocin is a possibility, but the drug must be used with caution. Too much oxytocin can cause unbearably strong contractions or a uterine rupture.

In the case of the female chinchilla pictured here and in the xray above, this was a first time delivery. She was two years old, and went into labor the morning of March 23rd, 2023. The kits were alive and moving at the onset of labor, however, there was a failure of progression. Despite hours of active labor, the kits had not moved down into the birth canal. After 2-4 hours of labor with no progress, the situation became more critical. The longer a delivery is delayed, the less likely it is that the kits will be born alive. An experienced owner or herd manager may attempt to turn the kits, or help pull the kits, but it takes skill and experience, and both carry risk. The administration of oxytocin is a possibility, but the drug must be used with caution. Too much oxytocin can cause unbearably strong contractions or a uterine rupture.

The female did not appear to be in extreme discomfort, so an x-ray was performed to rule out a deformity or an excessively large single kit. Two kits of normal size were seen on radiograph, so it was decided that the female would be left alone to attempt to deliver on her own. If a cesarean is a consideration, intervention is recommended after 2-4 hours of no progress. However, chinchillas often have a low survival rate following cesarean, so it was decided that she might have better odds if she could deliver on her own with more time. The female was monitored throughout the night, but there was still no progress and she was becoming visibly tired. She was taken into surgery at 8am the following morning.

Some of the added dangers of a delayed cesarean are exhaustion and dehydration on the part of the female - making her less able to survive a major surgery, and necrosis of the uterus and surrounding tissues which can lead to sepsis and subsequent death. In the case of this female, she was lucky and her uterus was still in good condition at the time of surgery. During the cesarean, the vet flushed her with a quinolone solution to help prevent a post surgical infection, and to hydrate her. Additionally, the vet inverted the sutures to the inside, to reduce pathogen transmission from the environment into the body cavity through the sutures. It was fortunate that there was not an advancement of necrosis to the skin which would have prevented the inversion. Regrettably, the kits had not survived. The two kits were in normal presentation position, but they were still relatively high in the body cavity and not descended into the pelvis as they should have been.

The female woke up from surgery in relatively good condition. The vet advised that all organic material be removed from the recovery cage. To minimize her stress, she was put back into in her own cage. Her stainless steel litter pan was sterilized, and a thick clean towel was placed over the pan. The towel was changed several times a day.

Surviving the actual surgery is only half the battle. Post op care is critical. If the chinchilla has a strong will to live, she will still need help. Pain medication was indicated for 4 days, and antibiotics for 7-8 days. Both of these medication can cause a loss of appetite and gut stasis. The consumption of water is essential. For the next several weeks, she was given water via syringe, and hand-fed a ground mixture of feed, flax seed, and Brytin probiotics mixed with water, every few hours. The first 4-7 days are the most critical, and the time the chinchilla is most likely to develop a life threatening post-surgical infection. During this time, the cage must be kept very clean, and stress should be kept to a minimum.

Surviving the actual surgery is only half the battle. Post op care is critical. If the chinchilla has a strong will to live, she will still need help. Pain medication was indicated for 4 days, and antibiotics for 7-8 days. Both of these medication can cause a loss of appetite and gut stasis. The consumption of water is essential. For the next several weeks, she was given water via syringe, and hand-fed a ground mixture of feed, flax seed, and Brytin probiotics mixed with water, every few hours. The first 4-7 days are the most critical, and the time the chinchilla is most likely to develop a life threatening post-surgical infection. During this time, the cage must be kept very clean, and stress should be kept to a minimum.

At 36 hours post op, she went through a concerning period of several hours during which the incision site was hot to the touch. However, the heat had mostly dissipated by the following morning. With great luck, overall she did well. She had a good attitude, and tolerated the forced eating and drinking. She felt slightly better after her pain medications and antibiotics were discontinued. She started eating some food on her own at 2-3 weeks post op. Her bedding was returned to normal at 3-4 weeks post op, and she was eating almost entirely on her own by 4 weeks post op. As a precaution and to help her heal from any stress, dietary, or medication-induced ulcers, she was offered alfalfa leaves starting 1 week post op (once it was fairly likely that her incision had closed). The alfalfa was continued for 6 weeks.

The herd veterinarian did a remarkably good job, giving Bonita a second chance at life!